A way to start software engineering

The realm of software engineering is complex. I intentionally say complex rather than difficult. The complexity makes a beginner feel perplexed, but there is a simple essence understanding, getting to which is the first, the hardest and the breaking through milestone. After the milestone is reached, all that is left is to unroll the complexity ball. And that is pretty straightforward and fun - you just read open-source, books, blog posts, tweets, watch conference talks and practice. Your learning becomes something proportional to the time you put into it.

Algorithmic articulation is the essence

Until you reach the milestone I say you need answers to none of the popular questions beginners bear searching answers with:

- what programming language to learn;

- what tooling to use;

- what platforms to learn to write programs for.

- what books to read;

Until you reach the milestone, you need not be involved with unneeded complexities. You will read no books, you will learn no programming languages, you will learn no software engineering. But you will learn to think algorithmically, formulate abstract solutions for the problem in your head and transform that thinking into something formal and strict - a programming language. Thus you will produce a program. The program will read some input data for the problem, will get executed instruction by instruction producing side effects and contributing into the final result and at the end it will show the result. I will highlight that the program doesn’t produce the solution but rather itself is the solution, which takes some parameters of the problem and produces the result for that problem with those parameters.

So, a program is a strictly formalized algorithm. Algorithm is a sequence of instructions, possible with branches and loops. Computer executes the instructions the effect of which produces the result with a meaning known to you - the author of the instructions - but not to the computer. Computer does not make sense of what it executes. You might make a mistake composing the instructions, and the computer still might successfully execute them producing a result, but only you will understand that the result is incorrect and unexpected. Only you will be able to review the instruction sequence (debug) trying to understand at which point you put an incorrect instruction making the calculations go the wrong way.

Getting to understand algorithms by examples

Let’s go through an example and it will be great if you have some mathematical background. The problem - you want to know the factorial of 12. The algorithm - you multiply all the numbers starting from 2 to 12 like this 2 x 3 x 4 x … x 11 x 12. If you were to calculate this on a piece of paper you would take 2, would multiply it by 3 and would write it down as an intermediate result. Then would multiply the intermediate result by 4 and write it down. You would go on until you would have reached 12 and at that point your intermediate result would be the final result. Now, let’s transform this thinking into something formal and strict - the C programming language. Here the code is.

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

unsigned int n;

scanf("%u", &n);

unsigned long int result = 1;

for (unsigned int i = 2; i <= n; ++i) {

result = result * i;

}

printf("%lld", result);

}

This piece of code might look hardly apprehensive, but it does just what is described above as the algorithm. At this point you don’t need to deeply understand each element of syntax and just remember some parts that will remain mysterious until later. Until later you have to remember that each of your programs start with #include <stdio.h> bringing the ability to read from the console (standard input) and to write into the console (standard output). Standard input is a way of putting data into your program and standard output is a way of getting results (data) out from your program. You have to remember that each of your programs will have just the main function where the program starts executing when you launch it - int main() { ... }. You have to remember that all instructions you put into your main function’s body - between the braces int main { ... } - get executed one by one. Until later you will compose only this part of the program. You will learn what is a variable declaration - in this program unsigned int n;, unsigned long int result = 1; and unsigned int i = 2;; how the values of variables get changed during the program execution maintaining intermediate results, in this program scanf("%u", &n);, ++i and result = result * i; what are loops, in this program for ( ... ) { ... }, what are branches, in this program implicitly as part of the loop syntax i <= n, meaning go into the loop body if the expression is true, else go outside it breaking the loop; what are arrays.

To compose programs you will use the Compiler Explorer tool. If you follow the link you’ll see the program code on the left panel and standard input and output on the right panel. You can change the value in the standard input field and see that the program produces for you the right result in the standard output field. This tool is interactive and you get results immediately as you change either the program code or the standard input.

Let’s have another example. Problem - find all prime numbers in the range [100;200]. Algorithm - you will take a number from the range and test whether it is divisible by any number less than itself not counting 1. If it has no divisors then it is a prime number and you should print it out. Then you’ll take another number from the range and repeat the calculations. You will go on until you exhaust the numbers in the range. If you were to make the calculations in your head for the number 101, you would test if it is divisible by 100 and would know it is not, then you would test if it is divisible by 99 and would know that it is not. You would go on until you reach 2 and see that 101 is not divisible by 2 as well. Then you would know that 101 is a prime number. Some tests might seem quite obvious to you, but the computer does not think and does not know things, therefore you have to spell out even the most obvious things. But you are right, some calculations really are redundant and you can avoid them without hurting the correctness of the algorithm. For example, there is no need to test whether 101 is divisible by any number greater than 50, because you know that there is no divisor for any number greater than itself divided by 2. So, for 101 you have only to test [2; 50] potential divisors. Let’s transform this thinking into the C programming language. Here it is

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int from;

int to;

scanf("%u %u", &from, &to);

for (int x = from; x <= to; ++x) {

int divisor_count = 0;

for (int divisor = 2; divisor <= x / 2; ++divisor) {

if (x % divisor == 0) {

divisor_count = divisor_count + 1;

}

}

if (divisor_count == 0) {

printf("%d\n", x);

}

}

}

Follow the link and play with your program. You can further optimize your program. Half of the numbers are even (parity in mathematics), so they are known not to be prime, therefore you can eliminate half of the calculations by skipping even numbers. Lets introduce this optimization into your program

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int from;

int to;

scanf("%u %u", &from, &to);

if (from % 2 == 0) {

from = from + 1;

}

for (int x = from; x <= to; x = x + 2) {

int divisor_count = 0;

for (int divisor = 3; divisor <= x / 2; ++divisor) {

if (x % divisor == 0) {

divisor_count = divisor_count + 1;

}

}

if (divisor_count == 0) {

printf("%d\n", x);

}

}

}

The branching construction

if (from % 2 == 0) {

from = from + 1;

}

ensures the program selects the first odd number from the range. And this little change ++x => x = x + 2 makes the x step by 2 rather than 1 skipping even numbers. Notice also that we changed int divisor = 2 to int divisor = 3, because we already skipped the even numbers.

There is another optimization. It is the axiom (or it might be a theorem with a proof) that no number has divisors greater than square root of itself. So, the testing range [3; 50] can be reduced to [3; √101] meaning to [3; 10]. Here is the modified program

#include <stdio.h>

#include <math.h>

int main() {

int from;

int to;

scanf("%u %u", &from, &to);

if (from % 2 == 0) {

from = from + 1;

}

for (int x = from; x <= to; x = x + 2) {

int divisor_count = 0;

for (int divisor = 2; divisor <= sqrt(x); ++divisor) {

if (x % divisor == 0) {

divisor_count = divisor_count + 1;

}

}

if (divisor_count == 0) {

printf("%d\n", x);

}

}

}

We changed divisor <= x / 2 to divisor <= sqrt(x). Also we added the line at the top #include <math.h> to bring the sqrt function into your program. Play with it.

Practice composing algorithms

Now, what to do next is practice composing programs like this until you feel you deeply get it. You will know when it happens. You will need some source of simple problems like our examples; you already have the Compiler Explorer tool to compose and run your programs; and you will need a way to validate that your programs produce expected answers to all possible inputs defined by the problems. Luckily there are online websites that have huge problem sets. You select a problem from such a website, write the program for the problem and submit the program to the website. The website will run your program with different inputs and will tell you whether your program always produces correct answers, and whether it is optimized enough and fits the time and memory constraints imposed by the problem.

Lets have a look at two such websites https://codeforces.com and https://www.geeksforgeeks.org. Select any of two and go practicing. When you don’t know how to express something in C programming language, luckily most of the problems have exemptions and available solutions (programs). Or you can reach someone out and just ask.

Let’s look at the Divisibility Problem from Codeforces. Here is the solution

#include <stdio.h>

int main() {

int t;

scanf("%d", &t);

while (t--) {

int a, b;

scanf("%d %d", &a, &b);

if (a % b == 0) {

printf("0\n");

} else {

printf("%d\n", b - a % b);

}

}

}

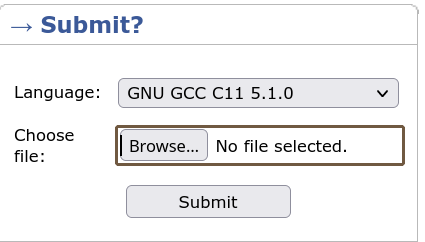

You save this code in a file, for example main.c. Then you submit the program for testing using the submission widget on the right side of the site

Right after you’ll see the results of your program testing.

This problem also has explanation and solution, you can find them on the Contest materials widget

To find a problem, you can go to Problem Set from the main page, sort the list in order of increasing difficulty and also filter in some specific topics, like Math.

The second option is GeeksForGeeks which also has a rich resource of tutorials with explanations and solutions.

For example, you can go to Tutorials->Algorithms->Mathematical then click on GCD and LCM and find a very thorough explanation of the topic. There is also the solution. Or you can go right into Practice->All DSA Problems and start solving.

Summary

Develop algorithmic thinking first. Practice algorithmic articulacy by solving pure algorithmic problems. Meanwhile, don’t get involved with engineering problems.

I’m sure you are perplexed, but I hope you are also excited.

Resources

Brilliant is an awesome learning platform. They have an article about Computer Programming Resources for Beginners. I was very surprised to read they suggest the same approach for learning programming - starting with practicing algorithmic thinking.